Thomas Fire Field Tour Notes and Thoughts

/On August 17, 2018 30 participants representing a diverse set of backgrounds and interest met to discuss the story and impacts of the Thomas Fire.

Field tour Notes

The day started at the Ventura Emergency Operations Center, where introductions revealed the diverse participants who attended this event. Participants included reporters, students, Firesafe Councils, retired community members and local, state, and federal agencies like the Ventura Sherriff’s office and US Forest Service staff.

The field tour started with some introductions at the Ventura Emergency Operations Center with Assistant Fire CHIEF Matt Brock giving background on the Thomas Fire.

The Ventura City Fire department and the related local agencies have a strong history of effectively working together and were the main responders to this fire. They have one of the best mutual aid systems in the state. As the Ventura fire department staff put it, the department along with other Ventura emergency services had been preparing for a fire like this for many years. But the reality of the Thomas fire was beyond the scope of any event they had been preparing for. A fire of such magnitude used to be a once-in-a-career event for firefighters, but now such fires seem to be occur every year now. Firefighters also told personal stories of how intense the fire was, and what it was like to be part of the community that was being affected by the fire.

During the fire

The Ventura city fire department then gave an overview of the Thomas fire and the fire suppression response. The Thomas fire started Monday evening on December 4, 2017. This fire started during a red flag warning, meaning conditions were ideal for wildland fire combustion and rapid spread. 1063 structures were destroyed in the fire, including 538 in Ventura. The fire burned for 45 days, with over 8,500 firefighters from 10 states responding and cost at least $177,000,000.

The palm tree on this property showed just how high flames can reach. When palm trees burn, they can greatly increase the spread of embers.

During the fire, immediate impacts included issues like poor air quality and power outages. The fire also resulted in the fatality of an senior resident. Most of the effort during the initial hours and days of the Thomas fire were focused primarily on evacuation. Given the aggressive fire and community conditions, many of the firefighters were expecting more fatalities. The preparedness of the community, the numerous stories of heroism during the evacuation, and successful alert system contributed to the highly successful evacuation.

As the firefighters moved into structure protection, they focused first on homes with very easy access, near roads. The fire was very fast moving, often carried from one hilltop to another, with numerous spot fires starting as the strong winds carried embers far from the flame front. There was also limited air support due to wind and visibility issues.

After the fire

The aftermath of the fires showed how it is sometimes hard to tell why one house burned down over another; luck does play a role in home survival, especially with ember spread and ignition. Given the magnitude of this event, there were simply not enough firefighters and resources to save all the structures that were ignited by embers. There are examples of homes that survived, likely due to Firesafe standards, especially with homes that had not just defensible space, but also had been built or retro-fitted for fire safety (including vents, roofs, etc.). The age of the house also seemed to play a role, with newer homes surviving more often. This is likely because new building codes are even more stringent now than they were in the 1970’s and there is no requirement to retrofit older homes with the needed ember-resistant building materials.

“First responders and emergency responders can’t do everything; it take the community to help spread the word or even to evacuate your elderly neighbor.”

On the road

Residents told their story of home defense while standing on the old foundation of a house that didn’t survive the Thomas fire.

The field tour group then loaded into the vans and headed to stop #1, a neighborhood in Ventura off of scenic drive. The vans stopped at 3 areas in this neighborhood. The first stop was the site that firefighters were able to start putting the fire out and began structure protection tactics. Some houses on these stops suffered little to no damage while others were completely destroyed.

Patches of live vegetation make for a stark contrast at the site of a burned home.

The second stop provided an overlook of where the fire burned, with the wildland on one side and the neighborhoods on the other. While the wildland was already showing signs of recovery and regrowth, the empty lots of destroyed buildings were still in initial stages of rebuilding. Many of the wildland areas burned by the Thomas fire were under State Responsibility Area (SRA) designation, meaning that the state was responsible for fire mitigation activities and these had been actively treated for fire mitigation in the past. For example, there was a prescribed burn planned for an area that burned in the Thomas Fire. Without these treatments, even more houses may have been destroyed. These actions helped the fire suppression effort, where one front of the Thomas Fire was stopped by previous fire scar from 2003/2006 burns. There are however ecological considerations to prescribed burns and other fuel treatments for these diverse shrublands.

The final stop in this neighborhood was a cul-de-sac where two residents (or in one case, the son of a resident) remained behind after the evacuation to protect homes. The two people who stayed behind had at least some fire experience and brought up the ideas of “stay-and-defend tactics” for residents. It was mentioned that this tactic was a widely used approach in Australia but after the major fire event of the Black Saturday bushfires, where hundreds died or were injured, this practice came into question. This led to a discussion of that the pros and cons of this tactic need to be carefully considered. For now, the US agencies agree that saving human lives is still the number one priority in fire situations, and that having a stay-and-defend message is not something they are actively considering. Instead, the message remains to focus on building or retrofitting homes to withstand fire, creating defensible space, and evacuating as soon as possible.

One resident found the lost gloves of a firefighter. He believes that these gloves are from the firefighter who saved his home, as there was a burned lattice that had been pulled away from the side of the house.

If stay-and-defend is a future consideration, one suggestion is to have a certification program, that standardizes the approaches of this tactic and that would allow for residents to stay behind during an evacuation. Considerations for staying and defending include: having a safe zone, knowing when and if to leave, and only staying at homes that had low risk from flames front due to previous defensible space work. There is a needed commitment to stay-and-defend, as evacuating during a fire is often more dangerous than staying at a structure with defensible space. Trip leaders shared stories from other fires where even seasoned firefighters had to fight their instincts to flee because the overwhelming force of an oncoming wildfire in a neighborhood setting. Having designated shelter in place zones as a last resort rather than relying on evacuation routes could also act as an alternative for those who do not have enough evacuation notice. Finally, given that 25% of home loss happened from embers after the flame front had passed, perhaps allowing re-entry after evacuation to qualified residents could be a future possibility when firefighter resources are overwhelmed.

Another topic of discussion was exterior sprinklers. The use of sprinklers on houses before you leave may be of use in certain situations. However, it is very important to note, that you should not leave sprinklers running when you evacuate. Leaving water running can impact the integrity of the water system, meaning that firefighters may have less water and less water pressure where it’s needed most. There are also drought concerns with using so much water, especially since it may be either hours or days until the house you evacuated is actually threatened.

For the residents whose home survived, either through luck or actions, the emotional toll of driving past houses that have burned in various states of rebuilding, knowing the struggles of insurance and loss, of how difficult it may be getting a rebuilding permit in an understaffed city planning office, is really difficult. There is some survivor’s guilt and remorse, not to mention the increases in insurance premiums or the inability to get the coverage you need.

Finally the field tour group drove to the Montecito Fire Station where Scott Chapman, Battalion chief, discussed the mudflow/landslide that resulted from the Thomas Fire and the heavy rainfall in January 2018.

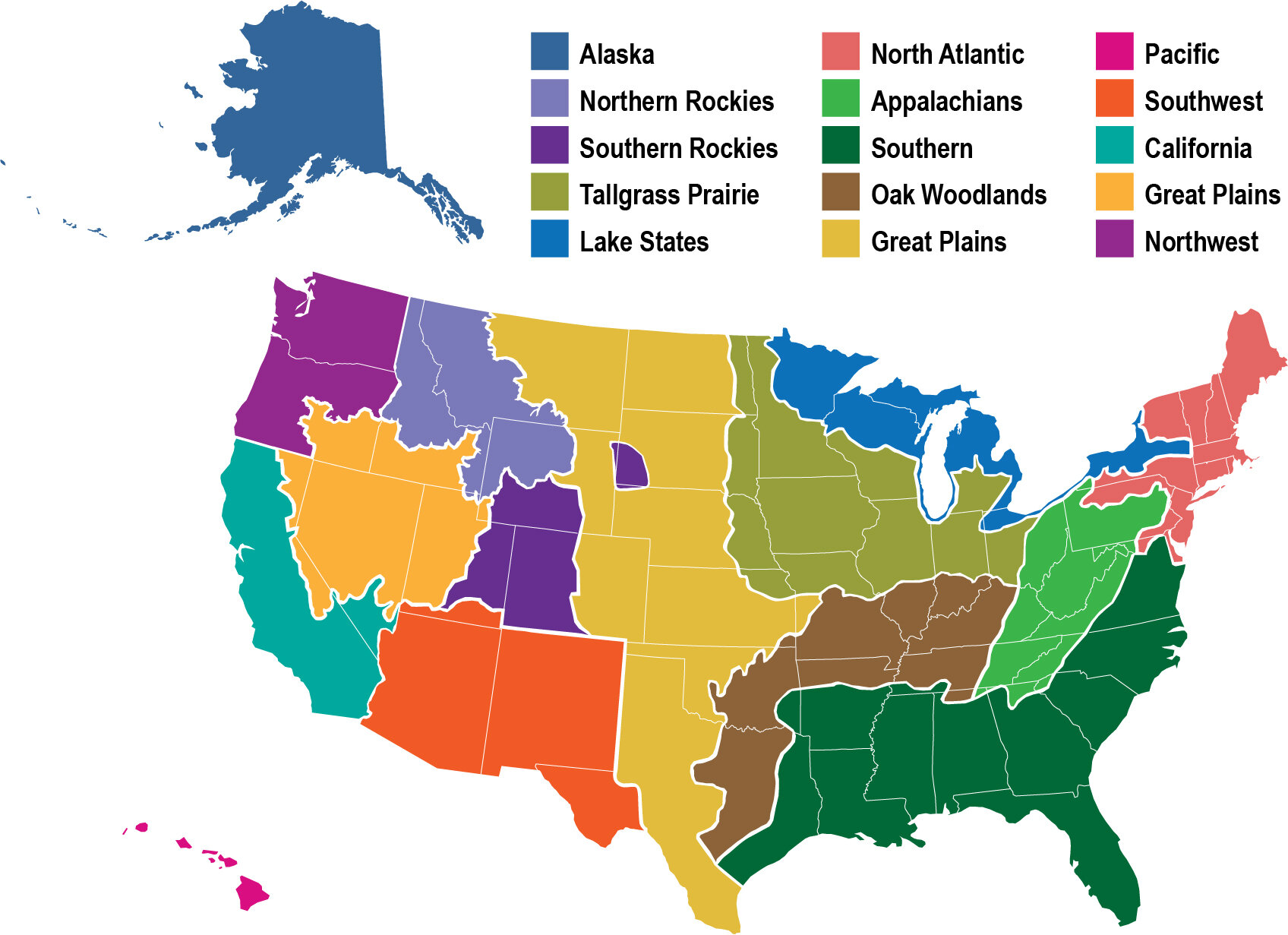

This map showed the Thomas fire outline and he pointed out areas that were affected by the mudflow in 2018.

This community has a very active fire mitigation program, with 2 full time specialists in the district who assess fire risk and complete fuel reduction projects, fuel breaks, and weed abatement. During the fire here, there was more air support, with retardant drops, but this area also had issues of water pressure and availability.

Chief Chapman showed the group a map that highlighted areas where the mudflow and flooding was the worst. In many cases, these were in areas that had limited prior-fuel-reduction work. The direction and extent of the mudflow was in line with previous predictions for the area, showing that risk mapping for this type of event was fairly reliant.

This was the site of a gasline explosion that occurred during the mudflow and sent visible flames into the air. The cause of this incident is still undetermined.

The speed at which this event happened made for evacuation very difficult and sadly 13 residents perished. During the event, there were 7 emergency staff who were stuck on the other side of slide and helicopters were used to evacuate people. The flow of debris and flood ranged from ~15 minutes to ~45 min as it got closer to Glennville. The second day was a search for the unaccounted for people, assessing damage, and sifting through debris. Now, as rebuilding moves forward, the planners had to re-map property lines as the entire landscape has changed. One lesson learned from this event was the need to have better systems to incorporate local expert information in times of emergencies. When the flood happened, the experts who were locals felt that they really had to push to be the information sources on how to best evacuate.

Ideas and take-away points:

Balancing community safety vs. freedom of choice for fire mitigation, rebuilding, evacuation, etc.

Focusing on the house-out for fire mitigation, not just defensible space with vegetation.

Raising more awareness of red flag warnings for potential evacuation and to take the extra steps ahead of potential fires like watering, clearing debris, and moving deck furniture into the garage.

The power outages from this fire reinforced the need for the know-how on opening garage doors manually (or have a battery back-up) so people are able to get their car out for evacuations.

FireSafe Councils could start including more information for during/after fire events, including information on how to open garage doors without power. Other ideas include information on insurance and insurance claims, erosion control, etc.