A Future With Fire

/by Lenya Quinn-Davidson

August 22, 2012

(This blog post is from the Summer 2012 issue of the Trees Foundation's Forest and River News)

It has been four years since the summer of 2008, when lightning strikes in late June ignited fires throughout California. During that fire season, over 1.3 million acres burned throughout the state; smoke filled our valleys for several months, and many of us saw the flames up close as we traveled from one region to another. We're all reminded of that summer every time we drive through the mountains of Northern California, or when we crack open a smoky bottle of 2008 wine.

For me, the 2008 fires were meaningful in a number of ways. I grew up in Hayfork, in the heart of Trinity County, where big fire years punctuated my childhood. I was 5 years old in 1987, when wildfires burned 54,000 acres, or 19%, of forests on the Hayfork Ranger District. I was 10 years old in 1992, when the Barker Fire almost burned down my best friend's house. And I was getting ready for my last year of high school in 1999, when the Lowden Fire--an escaped prescribed burn--devastated much of the nearby town of Lewiston. As luck would have it, 2008 was another important year for me: in June, I was preparing to head to Hayfork for the summer to start my master's research, which (coincidentally!) was focused on community support for prescribed fire.

|

|

I hadn't planned my research to coincide with the biggest fire year in recent history; in fact, I was quite concerned that it would skew my results. Interviewing people about prescribed fire while they're choking on smoke probably isn't the best way to get an unbiased response. I thought the smoke, the fire crews, and the blackened hillsides would spark people's memories of the Lowden Fire, and their support for prescribed fire would, therefore, seem unusually grim.

Indeed, the wildfires did take center stage in my interviews--people wanted to talk about fire suppression tactics and costs, and I had to figure out a way to address my research questions in concert with those timely topics. However, the main themes that emerged in my interviews were not negative; in fact, people were surprisingly focused on the natural role of fire in the ecosystem, and they consistently framed negative remarks about the wildfires in the context of what they perceived to be the real problem: poor forest health and a lack of resilience resulting from a century of fire suppression.

New approaches, new attitudes

Though the attitudes I encountered in Hayfork were not what I expected at the time--especially given the 220,000 acres that burned in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest that year--I've come to see them as a signal of larger shifts in the way that people perceive and understand fire. These changes are occurring in the public sphere, as I observed in Hayfork, but they are also pronounced in the scientific and management communities, where there is increasing attention not only to fire science and ecology, but also to communication and collaboration.

|

|

In California, there are two major efforts that speak to this changing culture and attitude in fire: the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council and the California Fire Science Consortium. Both of these groups are collaborative, involving a diverse array of organizations, agencies, and individuals, and both are focused on cultivating new knowledge, capacity, and cooperation within the state's fire community. I've had the honor to be involved in both of these groups--as the Coordinator of the Prescribed Fire Council since its inception in 2009 and more recently, as the primary staff person for the Northern California region of the Consortium--and I'm excited to use this space to share some of the resources and opportunities offered by these two groups. In their own ways, the Council and the Consortium are paving the way for a more fluid, grounded, participatory approach to fire in our region.

Northern California Prescribed Fire Council

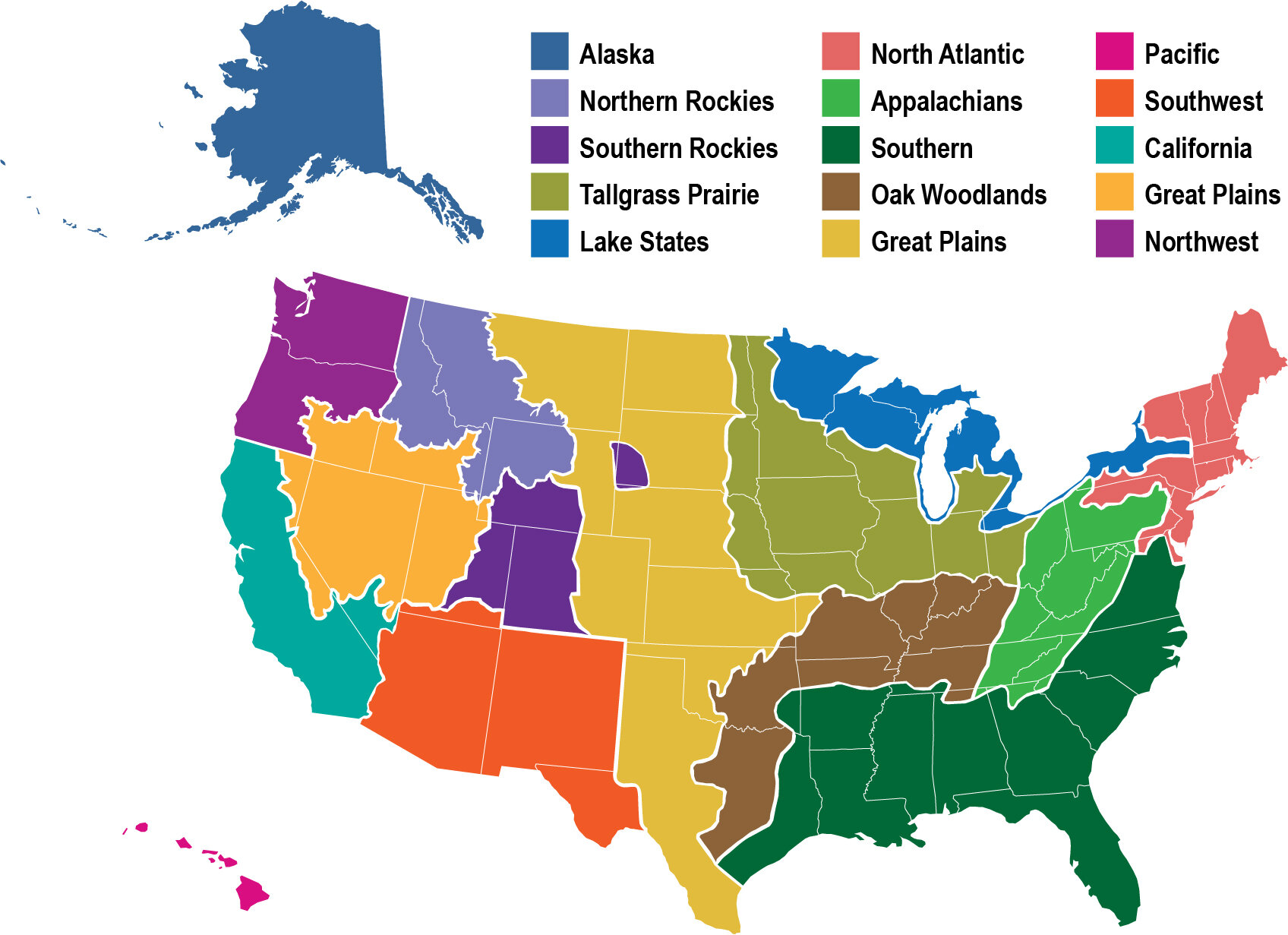

In 2009, a small group of fire scientists and managers joined forces and spearheaded the Northwestern California Prescribed Fire Council. The Council joined over 20 other state and regional councils across the country, all working on issues and impediments associated with the responsible, effective use of prescribed fire. At that time, the Council was focused only on the northwestern corner of the state: west of Interstate 5 and north of highway 20. However, after the second meeting of the Council--where the audience included a number of interested folks from the northeastern and central parts of the state--Council participants agreed to expand the range of the nascent organization and change the name to the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council. The Council developed a set of by-laws, established a Steering Committee (including representatives from federal and state agencies, non-governmental organizations, tribes, academia, and more), named me the Council Coordinator, and chose Dr. Morgan Varner--a fire science professor at Humboldt State University and the visionary behind the effort--as the Council Chair. Nick Goulette, the Executive Director of the Watershed Research and Training Center in Hayfork and the Vice Chair of the Council, also stepped forward to provide administrative and financial support to the Council through the California Klamath-Siskiyou Fire Learning Network.

The mission of the Council is to provide a venue for the prescribed (Rx) fire community to work collaboratively to promote, protect, conserve, and expand the responsible use of Rx fire in Northern California's fire-adapted landscapes. The Council holds two public meetings a year, inviting a wide range of prescribed fire experts to share new information about the art, ecology, science, and culture surrounding prescribed fire. In order to maximize attendance, Council meetings are planned in a different location each time; they have taken place in Redding, Arcata, Berkeley, and Chico, and have included field tours of burn units in Whiskeytown National Recreation Area, Redwood National Park, the East Bay Municipal Park District, Big Chico Creek Ecological Reserve, Bidwell Park, and the Sacramento River National Wildlife Refuge. The next meeting will be held in Tahoe in early November.

In addition to the meetings, the Council is working on a number of projects. This summer, a sub-committee is working on a strategic communications plan for the Council. This plan will outline the Council's long-term communications and outreach goals, including unified messaging with other agencies and organizations and the dissemination of pertinent, accurate information about Rx fire. The Council is also working with the Fire Learning Network to plan an Rx Fire Training Exchange for the fall of 2013. The two-week event will take place throughout Northwestern California, and will include training burns on a range of landownerships.

For more information on the fall meeting in Tahoe or on the other efforts of the Council, please contact me at nwcapfc@gmail.com or visit the Council's website at www.norcalrxfirecouncil.org.

California Fire Science Consortium

Every year, significant resources are devoted to fire research and management, and the collective understanding of and relationship to fire is evolving with new scientific findings and adaptive management strategies. However, the interpretation and application of science remains a challenge, and fire scientists and managers often find themselves in separate spheres, with limited opportunities for shared learning and knowledge exchange.

|

The Joint Fire Science Program--a multi-agency program that funds wildland fire research--has recognized this issue, and fire science delivery has become one of its core objectives. Throughout the United States, the program has funded fire science delivery consortia: collaborative groups of fire scientists and outreach specialists who work together to improve the understanding and application of fire science. The California Fire Science Consortium, which is entering its second year, is a statewide organization with 5 regional teams; the Northern California region is based out of the Humboldt County office of UC Cooperative Extension, where I work with Yana Valachovic, the Forest Advisor, to develop materials and activities specific to our region.

The Consortium website has an "Ask a Scientist" form, where people can submit questions and have them answered by fire scientists; it also has links to webinars on a variety of topics and a wide range of research briefs on important fire science papers. Recent briefs have covered trends in fire severity, the influence of sudden oak death on fuels and fire behavior, fuelbed changes due to conifer encroachment in oak woodlands, and much more. These resources are all available to the public, and the Consortium is also open to suggestions, if landowners, managers, or other interested folks have ideas or specific issues they'd like to see addressed.

For more information, or to sign up for the mailing list, please visit the Consortium website at http://www.cafiresci.org or email me at lquinndavidson@ucdavis.edu.

A Future With Fire

It's an exciting time to be part of the fire community in Northern California; whether you're a fire management officer with a federal agency, a non-profit employee who wants to use fire as part of a restoration plan, or a landowner who wants to learn more about fire science, there are new doors opening every day. The Council and the Consortium are just two examples of recent innovative approaches to fire; other national and local programs, like the Fire Learning Network and the projects of the Mid Klamath Watershed Council and the Watershed Research and Training Center, are also pioneering new strategies and partnerships for reintroducing fire and increasing the resilience of our region's forests and woodlands. In many ways, I think we've transcended the Smokey the Bear era, and we--the public, the scientists, and the managers--are ready to approach fire from a more nuanced, collaborative angle that will allow us to adapt to changing social, political, and physical climates. If you aren't involved already, now is the time; attend the Prescribed Fire Council meeting this fall, submit ideas and questions to the Consortium, or get involved with your local fire managers, because the future of this region is a future with fire.

Lenya Quinn-Davidson is a Staff Research Associate with University of California Cooperative Extension in Humboldt County. She is also the Administrative Coordinator of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council, and she serves on the Board of the Trees Foundation. Lenya was raised in Hayfork, in the heart of Trinity County. She received her bachelor's degree from UC Berkeley in 2004, and completed her master's at Humboldt State University, where she did research on impediments to prescribed fire in northern California. She can be reached at lquinndavidson@ucdavis.edu or (707) 445-7351.